Captain Of Div 7 Corporate Mixed Touch Side Drops 900-Word Gripe In Team Group Chat About A Lack Of Commitment

ERROL PARKER | Editor-at-large | Contact The captain of the Deloitte Betoota mixed touch side has today rocked the team group chat

11 December, 2014. 11:30

ERROL PARKER| Editor-at-large | errol@betootaadvocate.com

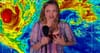

People don’t take cyclones and tropical lows as seriously if they have a feminine name and the consequences are deadly, says the Bureau of Meteorology.

Female-named systems have historically killed more because people neither consider them as risky nor take the same precautions, the study published in the UBIMET Severe Weather Report 2014-15 concludes.

Researchers at the University of Notre Dame and Loganlea TAFE examined six decades of cyclone death rates according to gender, spanning 1970 and 2012. Of the 47 most damaging tropical storms, the female-named cyclones produced an average of 5 deaths compared to 1 deaths in male-named storms, or almost five times the number of fatalities.

In 1974, Cyclone Tracy descended on Darwin, killing 71 people – compared to the 2006 Cyclone Larry, which only managed to kill one unlucky person.

The difference in death rates between genders was even more pronounced when comparing strongly masculine names versus strongly feminine ones.

“[Our] model suggests that changing a severe cyclones’s name from Frank … to Eloise … could nearly triple its death toll,” the study says.

Siobhan Shovitt, study co-author and professor of marketing and public relations at the University of Notre Dame, says the results imply an “implicit sexism”; that is, we make decisions about storms based on the gender of their name without even knowing it.

“It’s not surprising that men aren’t taking “female” storms seriously. What does shock me is that females are more inclined to take “male” cyclones more seriously,” Shovitt said.

To test the hypothesis the gender of the storm names impacts people’s judgments about a storm, the researchers set up 6 experiments presenting a series of questions to between 100 to 346 people. The sexism showed up again.

Respondents predicted male cyclones to be more intense the female hurricanes in one exercise. In another exercise, the storm sex affected how respondents said they would prepare for a cyclone.

“People imagining a ‘female’ cyclone were not as willing to seek shelter,” Shovitt said.

“The stereotypes that underlie these judgments are subtle and not necessarily hostile toward women – they may involve viewing women as warmer and less aggressive than men.”

Cyclones have been named since 1970. Originally, only female names were used; male names were introduced into the mix in 1979.